Another piece of Valletta is about to be improved.

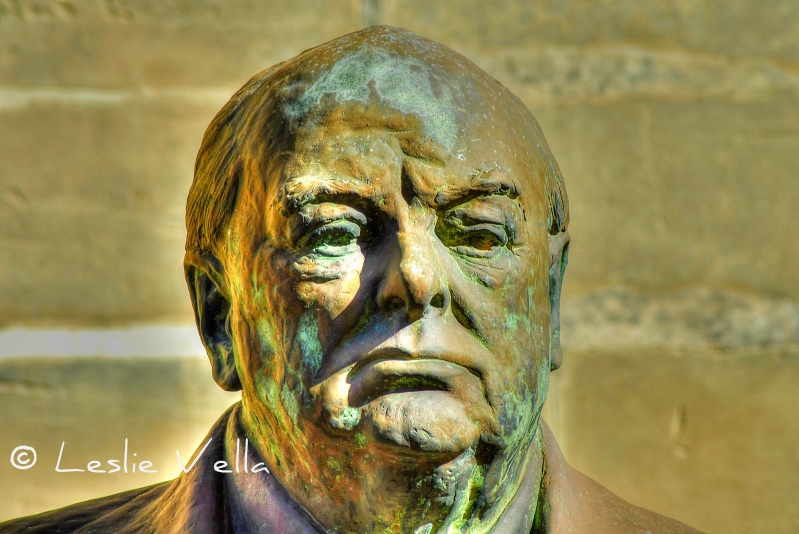

The scruffy, shanty-town collection of kiosks and bus ticket offices circling the perimeter of the former bus terminus which converges into the bridge crossing the dry moat to City Gate have already been closed down to be demolished to make space for a pedestrianized, tree lined plaza focused round Vincenzo Apap’s bronze masterpiece, the Tritons Fountain which is also set to be returned to its former operating glory.

Sounds fantastic. Rundown, dilapidated, downright ugly and nondescript structures selling a variety of cheap foodstuffs and convenience goods. With clients to match. To be replaced by a neater, well planned, uniformly designed layout in which the pedestrian is king.

The demolishing of these eyesores, ugly and unloved as they are, cannot but also raise a tinge of nostalgic regret in me. A nostalgia comprising half a century of memories of a location which is central to the lives of the majority of the Maltese. A location which for decades has served not only as the fulcrum of the Island’s public transport network, but also as the meeting point for friends, students, colleagues, lovers and countless other combinations of humanity.

A nostalgia based on memories of childhood, youth, love, friends, education, work and family.

For within those ugly structures lurked a world which shall not exist any more: some of which already has not existed any more for some years now.

A world comprising establishments such as the Milk Van and the Imqaret Kiosk. Both synonymous with their unique City Gate location. I have early childhood memories of drinking flavoured milk from a pyramidal carton purchased from that Milk Van. I also remember buying milk in glass bottles, fresh ricotta and yogurt from what was probably Malta’s only surviving stand-alone retail outlet exclusively selling dairy products.

The same Milk Van also served as the area’s ubiquitous Meeting Point. Meeting a girlfriend on a first date, a group of friends for a hike or a day at the beach or a visit to Valletta to go to the cinema or shopping generally involved meeting “near the Milk Van” at a specific date and time.

The Imqaret Kiosk: a ramshackle structure from which the enticing smell of deep-fried dates encased in golden pastry attracted people in droves to buy the ridiculously affordable, if unhealthy, deliciously warm and tasty heartburn bombs. The Kiosk operator would lure people to buy his wares by adding a few drops of anisette to the bubbling oil in which the mqaret were frying, and the resultant aroma had a pull not dissimilar to that of magnetism. Such was the brand value of the humble Imqaret Kiosk that other kiosks have sprouted elsewhere on the Island bearing the reassuring statement, “Imqaret minn tal-Belt” which translates into “same provenance as those of the Valletta kiosk”.

The Kiosks selling cheap pasti: fake kannoli filled with butter cream, atrociously coloured cakes containing a potentially lethal mix of food colourings and pies composed mostly of dough with the consistency of seasoned hardwood. And, from an age which predates one of the curses of our current age, plastic, the flavoured water dispensers from which orange or almond squash drinks could be purchased in real glasses which were returned to the kiosk for re-use. The same kiosks which remained open until the last bus left at 23:00 and which offered a telephone service for two cents a call when one missed the last bus and needed to do some explaining to one’s irate parents!

There were other shops too of course. I distinctly remember a news kiosk selling not only newspapers but also stocking a variety of glossy magazines, books and classics such as Marvel and DC comics which we would stop and look at in awe, penniless as we were as students. Carts selling deliciously smelling fresh bread in the morning, lottery ticket sellers and a variety of itinerant, enterprising seasonal sellers selling you umbrellas on a rainy day, vetch seeds for the Christmas crib in November, carob sweets during Lent, sandals and hats in summer. Apart from the then familiar but now rare sight of matronly ladies selling mulberries, capers, parsley, mint or bunches of stocks (gizi) from ancient prams. The scene was completed by the cheap souvenirs kiosk aimed at the panicking departing tourist who left it till last or bus passengers seeking a beach towel, a baseball cap or cheap sunshades!

Apart from all of these shops there were others less frequented. Shops which were attractive and provided sustenance to the bus and taxi drivers, bus conductors and ticket sellers. Burly men on metal chairs hunched on spindly formica tables drinking tea from a glass and eating a greasy pizza slice, a plate of imqarrun il-forn or a steaming qassata. A few rough looking ladies, bleach blonde and bedecked in garish jewellery made the picture complete. And in the narrow passageways behind the kiosks, another little world, not unlike Naples: unsavoury men betting money on card games or playing “morra”, a numbers guessing game which involved opening a number of fingers on one’s hands with the other side trying to guess a number from one to ten. Men who even the forces of law and order gave wide berth to.

The bulldozers shall be moving in soon. The structures will become but a distasteful memory from yesterday. Whatever will replace them will definitely be more visually attractive and appealing. But for nostalgics like me, the memory of what shall be no more shall always cause a small lump in my throat, a slight pressure in my chest whenever I pass from this well trodden patch of land.